Emily is a freelance writer in her late 30s. She has a partner, who is also self-employed as an IT consultant, and two small children. She is concerned about global warming and the environment and considers herself to be an ecologically conscious consumer. She believes in making ethical choices about the products and services she buys and the companies she buys from. She aspires to stay healthy and active, but she worries about the impact on her family finances if either she or her partner became sick and required medical treatment. She has started to think that having some form of health insurance cover would be sensible. She knows that if she or her family had a life-threatening illness the National Health Service would treat her, but she also knows that waiting lists are long for less urgent care. One of her children has asthma and Emily regularly visits or calls her primary care practitioner for advice on the best course of action. Her heart sinks as she contemplates how hard it will be to find health insurance coverage that suits her needs, is affordable and will meet her ethical principles. She has the bare minimum of legally mandated insurance for her car and house (bought through an online aggregator) and her interactions so far with insurance companies have been limited, but unimpressive.

Where does Emily start? She can compare benefit designs and pricing from many online aggregators and she can research the sustainability credentials trumpeted by the major insurance companies on their websites. As she looks, she becomes frustrated by the lack of a product tailored to her—one that recognises that she wants a health insurance product that does three things:

- Provides true insurance coverage for life’s catastrophe events that could impact her income and family security, while providing access to the health system for her and her family’s day-to-day health questions and issues.

- Recognises that she and her family make efforts to keep healthy—they have a good diet and prioritise exercise and mental health.

- Resonates with her as an eco-friendly product and service and an ethical brand. She is not clear what that might look like, but she knows she will recognise it when she sees it.

Point one is a matter of traditional health insurance benefit design—mixing high-frequency, low-severity benefits with low-frequency, high-severity benefits. Significant numbers of products now address point two, giving discounts or rewards to policyholders who maintain healthy lifestyles. But so far, with respect to point three, we have seen little of “green” or “sustainably focused” products in health insurance.

So what might resonate with our fictional Emily? I am going to examine some of the different facets of health insurance through an eco-friendly lens.

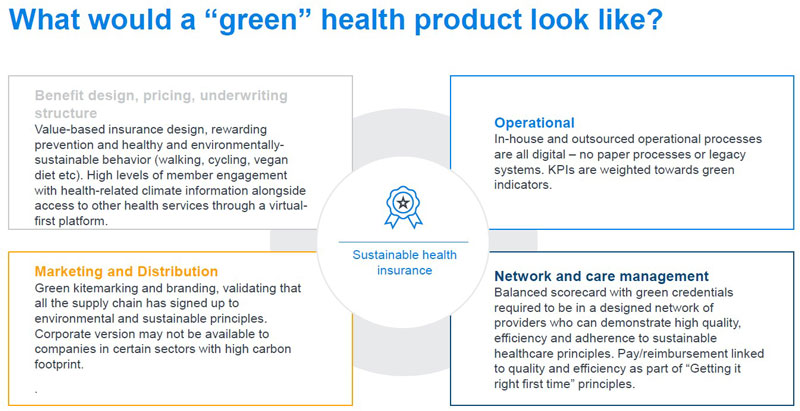

Benefit design, pricing, underwriting structure

The most obvious point is that the principles of value-based insurance design come heavily into play. Value-based insurance design prioritises services and benefits that are considered cost-effective over a long timeframe—for example, benefit designs that encourage and prioritise access to preventive services with no financial penalties for using those benefits. When drafting a schedule of health insurance benefits, copays and coinsurance, how are we thinking about climate-related events or diseases? If Emily or her family have a chronic disease caused or worsened by air pollution, or suffer ill health from a one-off acute climate event, such as a flood or accident, will her insurer help her put her family back on its feet, or will it impose excesses/deductibles, copays and coinsurances for essential services? Will the insurance design incentivise her to manage her daughter's asthma and keep the family members fit and their health status more resilient to climate change? Will the pricing and underwriting basis recognise that she is a health- and climate-conscious consumer who walks and cycles everywhere rather than drives and eats a primarily (but not totally) plant-based diet? Will the underwriting process recognise her daughter’s asthma as an opportunity to manage the family’s health going forward, or will it punish her by applying exclusions for asthma and related conditions?

Marketing and distribution

Emily may be attracted to a health insurance product that has a “green” branding, but what does that really mean? A sustainable Kitemarked product will need to show that all parts of the value chain have been thought through, from initial product design and pricing, to certifying distribution partners and sales channel for their eco-friendly credentials, to ensuring that advertising spend is well targeted and using appropriately sustainable channels. This is no small challenge for the average insurance product, which might be distributed through multiple channels, with thousands of brokers, as well as other parties not within the direct control of the insurance company. The placing of advertising is particularly problematic from a branding perspective, with significant potential for reputational damage if the placement ends up sitting beside other brands which do not have the same eco-credentials. Specialist distribution channels, which can reach affinity groups affiliated with ecological initiatives are one method, but they will limit the available market size to the insurer significantly.

Operational and management processes

Most insurance companies have their own climate change initiatives well under way—streamlining operational processes to increase efficiency has the added benefit, in most cases, of reducing carbon footprints as paper-based processes become digitised. However, in many health insurance companies there is still a way to go as legacy systems dominate underwriting, policy administration and claims processes. So what constitutes an eco-friendly set of operational processes? There are some basic principles:

- Operational resilience to climate-related events—both for the insurer and any outsourced operations

- Active monitoring and reporting of environment targets for operational processes

- Active management of carbon footprint from buildings and other infrastructure and people, including travel

- Active management of suppliers

These are very generic and not specific to health insurers in particular. However, the “active management of suppliers” is a key part of a green product because of the large carbon footprint of healthcare systems1—this is addressed in more detail below.

In addition, insurers will have to think about the investments they hold. While less relevant for short-term products like health insurance, this becomes highly relevant for long-term products like life insurance.

Network and care management

For most health insurers, helping their members navigate through the healthcare systems for advice, diagnostics and treatment is a key part of the value the insurer brings. While some insurers limit their interventions to maintaining a list of accredited providers, others actively manage the treatment pathway, steer patients towards favoured providers and provide specific services such as chronic care advice and management, population health interventions and member symptom checkers and general health education.

Most large healthcare systems have plans in place to reduce their large carbon footprints. Much of the direct environmental impact comes from patient transport and buildings infrastructure. The rise of telehealth-first appointments mitigates the carbon footprint, as well as initiatives around creating more sustainable buildings. Arguably however, the most important thing we can do from a sustainability perspective is to reduce the high levels of fraud, waste and abuse in provider systems. This is not new news, but risks being overshadowed and sidelined by initiatives which instead seek to reduce the carbon footprint of existing treatment pathways.

The “greenest” providers therefore are not necessarily those that have the best telehealth interface or remote monitoring capabilities or the newest physical plant, but those that are focused on getting the right care, right the first time, in the most efficient setting, eliminating duplicative tests and unnecessary and non-evidence-based diagnostics and interventions and that have the best outcomes from efficiency and patient perspectives. Put another way, if a provider routinely carries out surgical treatment that is contrary to evidence-based guidelines, that provider will have a greater environmental impact than its neighbouring provider which follows a more conservative best practice treatment pathway, but occupies an older more draughty building with limited focus on reducing emissions.

This brings an interesting conundrum for health insurers. How do they decide who to include in an environmentally “certified” network? They could simply include all providers who have signed up to certain environmental targets, or agree to comply with a supplier code of conduct. But that would seem a missed opportunity to drive better, more efficient outcomes for patients by creating a more nuanced, balanced scorecard for providers, recognising some of the trade-offs and potentially linking pay-for-performance reimbursement to that scorecard. In this way, a green network that offers a limited number of efficient providers with a digital first offering could offer significant cost advantages for a health insurer.

Insurers can also play a key role in providing care management, or even healthcare services, to patients in some systems. Forward-thinking insurers might consider how to partner with community resources to mitigate the impact of climate—for example through sponsoring cooling centres for members to access in areas of extreme heat. Insurers can also bring a focus on minimising the numbers of unnecessary services and physical visits as much as possible. This is highly pertinent to those insurers that are providing cross-border services, which often involve transporting patients by air to specialist centres of excellence.

Conclusion

How does all this help "Emily"? And, in fact, how many like Emily are even out there? Is there really a market for “green” health insurance and at what price?

Simply rebranding an existing offering—whether corporate, or consumer-focused—seems a missed opportunity (and a strategy that is doomed to fail in the long run). Similarly, trying to burnish an insurance company’s eco-credentials with generic statements and action without touching the product and proposition for consumers is unlikely to resonate with more climate-conscious consumers and will certainly not meet their climate-related health needs. Instead, a truly climate-friendly proposition needs to be rethought from the ground up, with all the different facets considered. Using the climate agenda as a way to gain a better handle on their health spend can potentially see lower claims cost inflation and better outcomes for patients. Insurers that think strategically about consumer needs and engage their supply chains in meaningful debate around this topic are far more likely to shape the market and be successful than those for whom climate change is an afterthought or simply a regulatory headache.

1Lenzen, P.M. et al. (July 2020). The environmental footprint of health care: A global assessment. The Lancet Planetary Health. Retrieved 25 June 2021 from https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(20)30121-2/fulltext.