Changing times: India's HI industry

The health insurance (HI) industry in India has evolved rapidly since the sector was opened to private players in the year 2000. Today, along with the four established public sector general insurance players, there are 18 general and six standalone private HI companies selling health coverage. The compound annual growth rate (CAGR) for gross premium in the HI industry has been 24.6% during the past 10 years (2005-2006 to 2014-2015). The high CAGR of the health segment has led to a noticeable rise in its overall share of nonlife premiums.

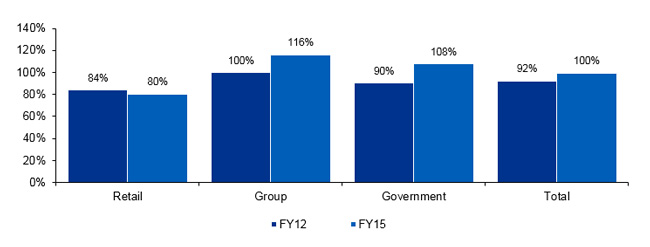

Figure 1: Incurred claims ratio

At the same time, as shown in Figure 1, the overall claims ratio has gone from 92% in financial year (FY) 2012 to 100% in FY 2015.1 This is a significant concern for India's HI industry.

To make matters more complicated, recent regulations have been more consumer-friendly, mandating guaranteed renewability, lifetime coverage and restricted premium revision opportunities.2 Also, the pre-existing disease (PED) exclusions have limited protection for an insurer. A pre-existing condition is a medical condition or disease existing before a health insurance policy is obtained. An insurance policy does not cover many PED conditions for up to four years of holding the policy. As the company experience matures, the PED exclusion protection wears off gradually and insurers rely on ever increasing amounts of new business to cross-subsidise existing books. This model is unsustainable in the long term.

For insurers, these new regulations imply that any substandard risk could potentially be retained for life. This implication necessitates a different approach to managing insurers’ growing portfolios. The countdown is on and insurers know it. There is growing anxiety about the potential looming impact. The existing prevalence of diabetes along with the rising incidence of diseases related to chronic or lifestyle-related issues are understandably fuelling high anxiety among insurers.

India also has unique challenges it must address in terms of public health. Public health services are inadequate–private sector primary care and outpatient care services are not well organised. Insurance companies cover inpatient hospital care only; they do not have direct control over nonhospital preventive or disease management services.

Changing gears: Population health analytics

It appears likely that those with insurance coverage will be looking to maintain it as long as they can by staying with the same insurance company. Insurers could benefit from beginning to treat their covered members utilising analytics based on population health principles. A population health approach requires a better clinical understanding of member populations in order to identify the most effective and cost-efficient strategies for managing their health and preventing hospitalisations and claims in the long run.

The three key questions insurers must ask with a population health approach are:

1. What is the current mix of my insured member population in terms of acute, healthy and chronic disease prevalence?

2. What are the current patterns of utilisation and costs among these different groups of member population?

3. What does the current portfolio mix imply for future medical expenses?

Answering these questions warrants a clinically focussed analysis to understand the potential risk in an insurer’s current member population and to understand cost drivers and trends over time. This segmentation can lead to useful and proactive population health management techniques.

Patient-centric clinical grouping

Here is an example of how population health analytics can work using a clinical grouping strategy. Milliman's Chronic Conditions Hierarchical Grouper (CCHG) tool enables patient-focused analysis that identifies population groups driving healthcare services utilisation trends in an insurer's portfolio. The grouper runs on diagnosis codes available in claims data (ICD-10) and has been successfully run in multiple markets.

Further, the tool has been adapted for India's unique circumstances, reflecting local coding patterns and particularly accounting for known limitations in the quality and depth of India's data. For example, existing ICD codes may be incomplete or available only to three digits with secondary diagnosis codes unavailable. In most cases, outpatient data is not available at all. Where possible, the CCHG tool is able to incorporate underwriting assessment data for an even more comprehensive identification of members with chronic diseases.

These levels of segmentation for a population health approach have multiple applications for insurers. Figure 2 is an illustration of some basic analytics for the CCHG groups. Understanding the current portfolio from a clinical analytics perspective will help insurers better define strategies to develop new products, realign risk appetite in underwriting new cases, prioritise medical management reinforcement in claims processing and/or identify prospects for disease management or wellness services.

For example, an insurer with an older-age portfolio with frequent claims will need to look at strengthening its claims management processes through changes to provider contracts, up-skilling of claims management staff, adoption of evidence-based pathways and protocols and closer monitoring of claims data. The CCHG tool is an invaluable resource in charting the way forward for insurers in these areas.

As another example, a company with a younger-age portfolio but with higher levels of chronic disease may need to consider additional benefits focused specifically on chronic disease management. Companies like this may want to look at providing value-added services, such as introducing a points- based reward system for preventive actions (e.g., preventive tests and check-ups, active weight management, smoking cessation and nutritional counselling), or limiting overseas coverage if applicable to reduce infrequent but high-cost claims. It might also need to consider realigning its risk appetite in medical underwriting for new member selection.

Figure 2: CCHG profile report (illustrative sample)

| CCHG category | Unique members | % Distribution chronic disease |

Inpatient admits/ 1000 |

Day case admits/ 1000 |

Average cost per year | Average premium per year | Loss ratio | Average age |

| Active cancer | 76 | 6% | 12.1 | 6.7 | 18,950 | 22,500 | 84% | 57 |

| Both CAD and diabetes | 69 | 6% | 4.3 | 2.5 | 16,580 | 26,200 | 63% | 69 |

| CAD without diabetes | 278 | 22% | 3.0 | 1.6 | 19,800 | 19,800 | 100% | 63 |

| Diabetes without CAD | 179 | 14% | 0.2 | 0.0 | 14,800 | 15,600 | 95% | 53 |

| Hypertension (incl. stroke and peripheral vascular disease | 61 | 5% | 0.4 | 0.2 | 13,650 | 14,800 | 92% | 63 |

| COPD | 54 | 4% | 0.2 | 0.0 | 18,700 | 28,200 | 66% | 75 |

| Asthma | 132 | 11% | 0.1 | 0.1 | 14,680 | 10,200 | 144% | 42 |

| Chronic musculoskeletal | 165 | 13% | 1.1 | 0.4 | 12,680 | 14,600 | 87% | 53 |

| Other chronic diseases (aggregated) | 232 | 19% | 1.4 | 0.5 | 8,650 | 9,680 | 89% | 46 |

| Health male (16-40) |

5,730 | 3.3 | 1.4 | 1,468 | 6,100 | 24% | 28 | |

| Healthy female (16-40) |

4,182 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 2,654 | 7,500 | 35% | 33 | |

| Healthy male (41-64) |

7,687 | 5.2 | 3.3 | 1,890 | 7,070 | 27% | 51 | |

| Healthy female (41-64) |

7,469 | 4.9 | 3.1 | 2,100 | 7,800 | 27% | 52 | |

| Healthy others | 6,267 | 4.0 | 2.3 | 3,680 | 12,600 | 29% | 67 | |

| Totals | 32,581 | 150,282 | 202,650 | 74% |

Sophisticated population health analytics enable insurers to make smarter and more informed decisions on financial trend drivers, and they can help medical management departments by more effectively allocating disease and care management resources. The CCHG is an ideal analytic tool for segmenting and stratifying populations into actionable cohorts.

Milliman experience

Milliman has worked on multiple projects utilising a population health approach in the United States, Asia and Europe. We have implemented and run clinical analytics of claims data to help companies and administrators understand and address the special needs of their members. Some of our key learning from segmenting members into meaningful clinical disease groups include:

- Insurance companies need to establish cost, resource utilisation and quality goals for specific populations of clinically similar patients.

- Many members can have claims in more than one disease group. This reflects the complex interaction that diseases have on one another. For example, a person with both coronary artery disease (CAD) and diabetes will have a different cost and utilisation experience than a person with just CAD or just diabetes.

- Because different diseases progress differently, it is important to identify the presence and prevalence of each disease in order to understand what will drive future medical expenses.

- It is important to differentiate chronic disease utilisation and cost trends from those driven by acute episodes. Individuals with chronic diseases can have large claims, but they could be for acute conditions that are not likely to cause future high cost–for example, trauma or pregnancy.

- Claims patterns for healthy individuals with no chronic conditions must be analysed as well.

Milliman can help guide insurers forward as India's HI industry continues to grow and change. To learn more, contact Lalit Baveja at [email protected].

1IRDA (2015). IRDA Annual Report 2014-15. Retrieved December 1, 2016, via https://www.irda.gov.in/ADMINCMS/cms/frmGeneral_NoYearList.aspx?DF=AR&mid=11.1.

2Taxmann (August 3, 2016). IRDA notifies regulations on Health Insurance. Retrieved December 9, 2016, from https://www.taxmann.com/topstories/104010000000048780/irda-notifies-regulations-on-health-insurance.aspx. Note specifically section 12 (Entry and Exit Age), section 13 (Renewal of Health Policies…), and section 25 (Loadings on Renewals).